Can you obtain a valid pwnyOS activation key?

By: arxenix

Attachments: handout.tar.gz

pwnykey is a simple flag checker - er… CD key checker. Type in key, check if it’s valid or not. The web server itself is pretty simple: It checks if the key is the right format, and if it is, it passes it to DeviceScript’s simulator and runs a program there. I had looked into DeviceScript a few weeks ago, so I already knew how it worked. It’s TypeScript for microprocessors (similar to MicroPython). The key checker is in keychecker.devs which is DeviceScript bytecode.

Disassembling the code

The DeviceScript CLI has its own disassembler (npx devicescript disasm), so let’s take a look at it disassembled.

// img size 12416

// 14 globals

proc main_F0(): @1120

locals: loc0,loc1,loc2

0: CALL prototype_F1()

???oops: Op-decode: can't find jump target 10; 0c

7: RETURN undefined

9: JMP 39

???oops: Op-decode: stack underflow; 4c

???oops: Op-decode: stack underflow; 250003

???oops: Op-decode: can't find jump target 22; 0c

19: RETURN undefined

???oops: Op-decode: can't find jump target 51; 0c

23: CALL ???oops op126(62, ret_val())

???oops: Op-decode: can't find jump target 34; 0c

31: RETURN undefined

???oops: Op-decode: can't find jump target 72; 0c

???oops: Op-decode: stack underflow; 02

???oops: Op-decode: stack underflow; 253303

???oops: Op-decode: can't find jump target 46; 0c

43: RETURN undefined

45: JMP 89

???oops: Op-decode: stack underflow; 1b34

???oops: Op-decode: stack underflow; 02

???oops: Op-decode: can't find jump target 57; 0c

54: RETURN undefined

...

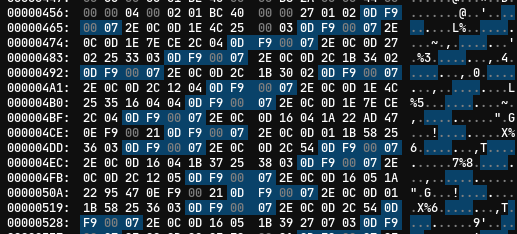

Uh oh, disassembly errors. DeviceScript’s disassembler isn’t very clear about what’s the problem, but after looking at the bytes by hand I realized that the can't find jump target lines are jump instructions that just aren’t being printed because they point towards the middle of a different instruction (according to the disassembler).

These 0D F9 00 07s are the culprit. It means “jump forward 7 bytes from the start of the instruction”, so the three bytes that follow a jump are always skipped over. Of course, the solution is to just NOP them out! I’m not sure how I thought 00 would work since the bytecode file lists this as invalid, but it seems to count as a single byte instruction we can use to patch up the holes.

import re

d = open("keychecker.devs","rb").read()

d = re.sub(b'\x0D\xF9\x00\x07...', b'\x0D\xF9\x00\x07\x00\x00\x00', d)

f = open("keychecker_patch.devs","wb")

f.write(d)

f.close()

Disassembling, we get the fixed program:

// img size 12416

// 14 globals

proc main_F0(): @1120

locals: loc0,loc1,loc2

0: CALL prototype_F1()

3: JMP 10

7: DEBUGGER

8: DEBUGGER

9: DEBUGGER

10: CALL ds."format"("start!")

15: JMP 22

19: DEBUGGER

20: DEBUGGER

21: DEBUGGER

22: CALL ds."print"(62, ret_val())

27: JMP 34

31: DEBUGGER

32: DEBUGGER

33: DEBUGGER

34: CALL fetch_F2("http://localhost/check")

39: JMP 46

43: DEBUGGER

44: DEBUGGER

45: DEBUGGER

46: CALL ret_val()."text"()

50: JMP 57

54: DEBUGGER

55: DEBUGGER

56: DEBUGGER

57: CALL ret_val()."trim"()

61: JMP 68

65: DEBUGGER

66: DEBUGGER

67: DEBUGGER

...

I modified the script to replace the useless JMP instructions with DEBUGGER as well, then deleted any lines from the disassembly that contained DEBUGGER in them. A little risky since really JMP instructions might get replaced, but after a quick look over, nothing seemed broken.

Reading the code

proc main_F0(): @1120

locals: loc0,loc1,loc2

0: CALL prototype_F1()

10: CALL ds."format"("start!")

22: CALL ds."print"(62, ret_val())

34: CALL fetch_F2("http://localhost/check")

46: CALL ret_val()."text"()

57: CALL ret_val()."trim"()

68: {G4} := ret_val()

78: CALL ds."format"("fetched key: {0}", {G4})

92: CALL ds."print"(62, ret_val())

104: JMP 143 IF NOT ({G4}."length" !== 29)

121: CALL (new Error)("Invalid key")

134: THROW ret_val()

143: CALL {G4}."split"("-")

157: {G5} := ret_val()

167: JMP 206 IF NOT ({G5}."length" !== 5)

184: CALL (new Error)("Invalid key")

197: THROW ret_val()

206: CALL {G5}."some"(inline_F7)

220: JMP 254 IF NOT ret_val()

232: CALL (new Error)("Invalid key")

245: THROW ret_val()

254: CALL {G5}."some"(CLOSURE(inline_F8))

268: JMP 302 IF NOT ret_val()

280: CALL (new Error)("Invalid key")

293: THROW ret_val()

302: CALL ds."format"("key format ok")

314: CALL ds."print"(62, ret_val())

326: CALL {G5}."map"(CLOSURE(inline_F9)) // par0.split().map(x => "0123456789ABCDFGHJKLMNPQRSTUWXYZ".indexOf(par0))

340: loc0 := ret_val()

350: {G6} := loc0[0]

363: {G7} := loc0[1]

376: {G8} := loc0[2]

389: {G9} := loc0[3]

402: {G10} := loc0[4]

...

Finally, readable code. This part is easy enough to understand. Split the string at - into five chunks, map each digit/letter to a number 0-31, then chuck the five groups of five numbers into G6-G10. I added a comment with the contents of inline_F9 so you can see how they map.

415: CALL ds."format"("{0}", {G6})

429: loc0 := ret_val()

439: ALLOC_ARRAY initial_size=5

448: loc1 := ret_val()

458: loc1[0] := 30 // Y

470: loc1[1] := 10 // A

482: loc1[2] := 21 // N

494: loc1[3] := 29 // X

506: loc1[4] := 10 // A

518: CALL ds."format"("{0}", loc1)

532: JMP 569 IF NOT (loc0 !== ret_val())

547: CALL (new Error)("Invalid key")

560: THROW ret_val()

569: CALL ds."format"("passed check1")

581: CALL ds."print"(62, ret_val())

The first check is easy. G6, the first five characters in number form are compared with another list of numbers. [30,10,21,29,10] maps to YANXA, so that’s the first five down.

593: CALL concat_F10({G7}, {G8})

607: {G11} := ret_val()

617: CALL {G11}."reduce"(inline_F11, 0) // (a,b) => a+b

632: loc0 := (ret_val() !== 134)

645: JMP 687 IF NOT !loc0

659: CALL {G11}."reduce"(inline_F12, 1)

674: loc0 := (ret_val() !== 12534912000) // (a,b) => a*b

687: JMP 722 IF NOT loc0 // 5DZU5H3M86

700: CALL (new Error)("Invalid key")

713: THROW ret_val()

722: CALL ds."format"("passed check2")

734: CALL ds."print"(62, ret_val())

The next check is pretty easy too. The second and third group of numbers are concat’d into G11. To pass, their sum has to be 134 and product has to be 12534912000. A simple Z3 script can find a solution:

from z3 import *

chars = '0123456789ABCDFGHJKLMNPQRSTUWXYZ'

nums = [BitVec(f'{i}', 32) for i in range(10)]

s = Solver()

for num in nums:

s.add(And(num >= 0, num < 32))

s.add(Sum(nums) == 134)

s.add(Product(nums) == 12534912000)

res = s.check()

if res == sat:

model = s.model()

values = ''.join([chars[model[element].as_long()] for element in nums])

print(values)

This prints out 5DZU5H3M86 for me now, although there are other solutions I found earlier.

Pretty easy so far, let’s see what’s last.

746: CALL concat_F10({G9}, {G10})

760: {G12} := ret_val()

770: {G13} := 1337

783: loc2 := 0

793: JMP 845 IF NOT (loc2 < 420)

811: CALL nextInt_F13()

821: loc2 := (loc2 + 1)

834: JMP 793

845: ALLOC_ARRAY initial_size=3

854: loc0 := ret_val()

864: CALL nextInt_F13()

874: loc0[0] := ret_val()

886: CALL nextInt_F13()

896: loc0[1] := ret_val()

908: CALL nextInt_F13()

918: loc0[2] := ret_val()

930: CALL ds."format"("{0}", loc0)

944: loc0 := ret_val()

954: ALLOC_ARRAY initial_size=3

963: loc1 := ret_val()

973: loc1[0] := -545529122

990: loc1[1] := -719079436

1007: loc1[2] := 1382093522

1024: CALL ds."format"("{0}", loc1)

1038: JMP 1075 IF NOT (loc0 !== ret_val())

1053: CALL (new Error)("Invalid key")

1066: THROW ret_val()

1075: CALL ds."format"("passed check3")

1087: CALL ds."print"(62, ret_val())

1099: CALL ds."format"("success!")

1111: CALL ds."print"(62, ret_val())

1123: RETURN 0

And nextInt looks like this:

proc nextInt_F13(): @5184

locals: loc0

0: CALL {G12}."pop"()

12: loc0 := ret_val()

22: loc0 := (loc0 ^ ((loc0 >> 2) & 4294967295))

41: loc0 := (loc0 ^ ((loc0 << 1) & 4294967295))

60: loc0 := (loc0 ^ (({G12}[0] ^ ({G12}[0] << 4)) & 4294967295))

86: {G13} := (({G13} + 13371337) & 4294967295)

106: CALL {G12}."unshift"(loc0)

120: RETURN (loc0 + {G13})

In JavaScript, that would look like this (theArray is the concatenation of the last two group of five numbers, G9 and G10):

var G12, G13;

function decodeThird(theArray) {

G12 = theArray;

G13 = 1337;

for (var i = 0; i < 420; i++) {

nextInt();

}

var a = [nextInt(),nextInt(),nextInt()].toString();

var b = [-545529122,-719079436,1382093522].toString();

return a == b;

}

function nextInt() {

loc0 = G12.pop();

loc0 = (loc0 ^ ((loc0 >> 2) & 0xffffffff));

loc0 = (loc0 ^ ((loc0 << 1) & 0xffffffff));

loc0 = (loc0 ^ ((G12[0] ^ (G12[0] << 4)) & 0xffffffff));

G13 = ((G13 + 13371337) & 0xffffffff);

G12.unshift(loc0);

return loc0 + G13;

}

Oof, I hope nextInt will be reversible. Brute forcing 10 five-bit numbers might be tough. I let Copilot generate most of the code to solve this one:

from z3 import *

def nextInt(G12, G13):

loc0 = G12.pop()

loc0 = (loc0 ^ (((loc0 >> 2)))) & 0xffffffff

loc0 = (loc0 ^ ((loc0 << 1))) & 0xffffffff

loc0 = (loc0 ^ ((G12[0] ^ (G12[0] << 4)))) & 0xffffffff

G13 = ((G13 + 13371337) & 0xffffffff)

G12.insert(0, loc0)

return (loc0 + G13) & 0xffffffff, G13

def decodeThird(theArray):

G12 = theArray

G13 = BitVecVal(1337, 32)

for x in range(420):

_, G13 = nextInt(G12, G13)

items = [

0xDF7BE2DE, #-545529122,

0xD523B7F4, #-719079436,

0x526112D2 #1382093522

]

conds = []

for x in range(3):

ret, G13 = nextInt(G12, G13)

conds.append(ret == items[x])

return And(conds[0], conds[1], conds[2])

theArray = [BitVec(f"theArray_{i}", 32) for i in range(10)]

solver = Solver()

for element in theArray:

solver.add(And(element >= 0, element < 32))

solver.add(decodeThird(theArray))

res = solver.check()

print(res)

if res == sat:

model = solver.model()

values = [model[element].as_long() for element in theArray]

print("Solution found:")

print(values)

else:

print("No solution found.")

Z3 either quits after a few minutes with unknown, or goes on forever using all of my disk space in the pagefile. Guess it couldn’t be that easy, so I had to come up with a better way to reverse this.

I searched around a bit trying to find the name of the nextInt function, even giving ChatGPT/Bing chat the code, but couldn’t find it. At the end of the competition, someone told me it could be found on this Wikipedia page on xorshift, although I don’t think knowing it was xorwow would’ve helped me in the end.

(I also tried writing a Rust program to randomly brute force inputs in hope there was a collision somewhere, but that got me nowhere after 24 hours.)

Further analysis on the third part

So what’s going down step by step in nextInt?

Imagine our last 11 characters of input were 01234-56789. G12 or theArray would look like [0,1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9].

- Pop last value (9 in this case) from the end of the array and store it into

loc0. - Do xor and shift stuff involving

loc0and the first value in the array (0 in this case). - Insert the result at the beginning of the list.

- Return the first value +

G13, the counter. - Repeat with 8 and whatever 9 became, then 7 and whatever 8 became, and so on 420 times…

- Compare the next 3 return values to check for the right input.

The counter can be pretty much ignored since it can be precalculated based on round count (421, 422, 423) and doesn’t involve the state array. I tried giving Z3 the precalculated values, but it didn’t speed anything up.

def g13_offset(val, off):

return (val - (1337+13371337*off)) & 0xffffffff

So it can’t figure out 420 states, but can Z3 figure a smaller amount like 20? I ran the original code with [0,1,2,3...] and 20 + 3 rounds. Sure enough, after a few minutes Z3 can reverse it… but it gave me back a different (yet still valid) result. That’s not good, the solution isn’t unique (which isn’t that surprising, but still annoying.) I also removed the 0-31 restriction and upped the rounds to a few hundred and got a solution. Oh no. We have to somehow find a solution that not only results in the last three xorwow results being specific ones, but we also have to make sure the input is only 0-31. How is this even possible?

Step by step

Assuming Z3 could find the a valid state using the last three return values, I tried to see if I could reverse a state of 10 numbers to the previous state (in other words, work backwards 10 loops of calling nextInt). In my own version of the original DeviceScript code (which I’ll call the “simulation”), I printed out G12 every 10 loops to see how the state changed over time and to compare with what Z3 came up with. So, I let Z3 rip and it returned some values:

# z3 result: [233568067, 706642777, 254311356, 772947471, -2109889853,

# 1561025182, -2016093499, 1902351517, 91078566, -117182616]

# simulation: [233568067, 706642777, 254311356, 772947471, 2109889852,

# -1561025183, 2016093498, 1902351517, 91078566, 117182615]

Interesting! It’s very close but only differs in the fact that some numbers are the bitwise negation of each other (e.g. ~2109889852 == -2109889853). Hmm, we might be on to something here! Z3 returned a few more results after a few minutes, but all of the other answers are just negations of random numbers, so it might be possible that those are the only options.

I ran my Z3 script on both the previous Z3 result and the simulation result and compared with the simulation result.

# z3 result on prev z3 result: [-1690675720, -1535914621, 1432309505, 1646652143, -73862263,

# -2113058402, -1286497377, -408567564, -801144163, -1497032086]

# z3 result on prev simulation: [ 1690675719, 1535914620, -1432309506, 1646652139, 1076054070,

# 968290849, 149561380, 408567563, 801144166, 494838229]

# simulation: [ 1690675719, 1535914620, 1432309505, 1646652139, 1076054070,

# 968290849, 149561380, 408567563, -801144167, 494838229]

Got my hopes up too fast. The Z3 script on the previous Z3 result starts to diverge hard. Looks like we need to have the right negations of each number to keep going down the right path.

Is this even possible?

I looked into negating inputs in [0,1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9] and found that all of them can be negated but the first number and keep the same last three numbers. I can’t remember what it was (xor or add), but you can do something to the last number to allow negating the first number as well. So that means you can have 2^10 or 1024 ways to get to a state. That means (if my math is correct) there are 1024^420 possible answers to arrive at our final state. In other words, you have to pick the right combination of negations (1/1024) 420 times to get back to the original value.

And wait, aren’t there only 4294967296^10 options for the state? 1024^420 is way bigger!

By this point I’m starting to question if this is possible. I try seeing if the z3 results can be transformed into the simulation results, but I can’t come up with anything to make that work. There’s no way to work backwards and eliminate options that produce inputs that aren’t 0-31 without going all the way, and then you’d just have brute force. You can’t go forwards because you don’t know which options get you to the last three numbers. In other words, there’s no indicator that tells you which is the right path to take.

At this time, the challenge was at 7 or 8 solves and I felt a bit discouraged. Obviously it’s hard since the other challenges have around 20-40 solves, but I couldn’t figure out what I missed. It was starting to feel more like a crypto challenge and less like a reverse engineering one.

I found a few more interesting things later, like the fact that most inputs aren’t reversible. So starting at the last three numbers at 423 and going back more than 423 would have Z3 spit out unsat no matter the solution. So each state “encodes” the “depth” somehow. While interesting, it doesn’t end up being useful.

The solution

Competition is over. It’s killing me. What did everyone else do?

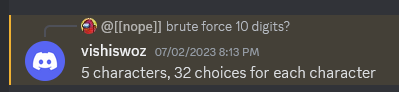

Uh… you brute forced 32^10 options?

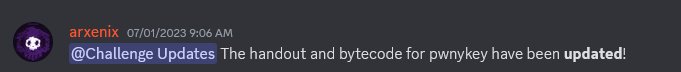

Oh no. Was it just ignoring the last 5 characters and I read it wrong? That would be funny.

389: {G9} := loc0[3]

402: {G10} := loc0[4]

...

746: CALL concat_F10({G9}, {G10})

760: {G12} := ret_val()

No, it’s definitely concatenating G9 and G10.

Oh no.

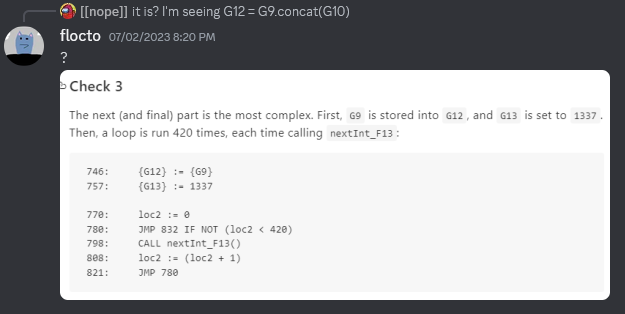

The challenge updated didn’t it. Sure enough, this was in #chal-updates:

I wasn’t part of the challenge update roles (hidden away in Discord’s new “Channels & Roles” channel) so I didn’t get the ping. Plus, the challenge description and file name wasn’t changed. So I had no idea it got updated.

Let’s… download the new version and see how it looks.

746: {G12} := {G9}

757: {G13} := 1337

770: loc2 := 0

780: JMP 832 IF NOT (loc2 < 420)

798: CALL nextInt_F13()

808: loc2 := (loc2 + 1)

821: JMP 780

832: ALLOC_ARRAY initial_size=3

841: loc0 := ret_val()

851: CALL nextInt_F13()

861: loc0[0] := ret_val()

873: CALL nextInt_F13()

883: loc0[1] := ret_val()

895: CALL nextInt_F13()

905: loc0[2] := ret_val()

917: CALL ds."format"("{0}", loc0)

931: loc0 := ret_val()

941: ALLOC_ARRAY initial_size=3

950: loc1 := ret_val()

960: loc1[0] := 2897974129

973: loc1[1] := -549922559

990: loc1[2] := -387684011

1007: CALL ds."format"("{0}", loc1)

1021: JMP 1058 IF NOT (loc0 !== ret_val())

1036: CALL (new Error)("Invalid key")

1049: THROW ret_val()

1058: CALL ds."format"("passed check3")

1070: CALL ds."print"(62, ret_val())

1082: CALL ds."format"("success!")

1094: CALL ds."print"(62, ret_val())

1106: RETURN 0

Great, it’s just five characters. Like everyone else said, it can just be brute forced.

fn do_thing(g12: &mut [i32], x: usize) -> i32 {

let j = (420 - x) % 5;

let i = ((420 - x) + 4) % 5;

let mut loc0 = g12[i];

loc0 = loc0 ^ ((loc0 >> 2) & -1);

loc0 = loc0 ^ ((loc0 << 1) & -1);

loc0 = loc0 ^ ((g12[j] ^ (g12[j] << 4)) & -1);

g12[i] = loc0;

return loc0;

}

const CHARS: &str = "0123456789ABCDFGHJKLMNPQRSTUWXYZ";

fn main() {

for e in 0..32 {

for d in 0..32 {

for c in 0..32 {

for b in 0..32 {

for a in 0..32 {

let mut arr: [i32; 5] = [a,b,c,d,e];

for x in 0_usize..420_usize {

do_thing(&mut arr, x);

}

// I've added the precalculated G13 values here

let x = do_thing(&mut arr, 0) + 1334366918;

if x != -1396993167 {

continue;

}

let y = do_thing(&mut arr, 1) + 1347738255;

if y != -549922559 {

continue;

}

let z = do_thing(&mut arr, 2) + 1361109592;

if z != -387684011 {

continue;

}

let good_arr: [i32; 5] = [a,b,c,d,e];

let ans: String = good_arr.iter().map(|&index| CHARS.chars().nth(index as usize).unwrap()).collect();

println!("done! {}", ans);

return;

}

}

}

}

}

}

After a little time, we get this:

done! FBP2U

Putting that into the key, we get YANXA-5DZU5-H3M86-FBP2U-AAAAA, which gives us the flag uiuctf{abbe62185750af9c2e19e2f2}.

Finding the last 5 characters

Assuming the key stayed the same after the change, we should be able to brute force the last 5 characters using FBP2U with the old three target numbers.

done! FBP2U0ANCZ

We’ve done it! We “cheated” a little bit, but the final answer is YANXA-5DZU5-H3M86-FBP2U-0ANCZ.

Talk about a difficulty curve from stages 1 and 2 to 3, LOL.

Also, here’s the updated handout. I didn’t post the updated one up front to not reveal there were two versions.